Initial Musings: Twain and Octavia Butler

The first time something spilled from Bruce's fingers to Substack: 14 Feb 2025

Starting Somewhere:

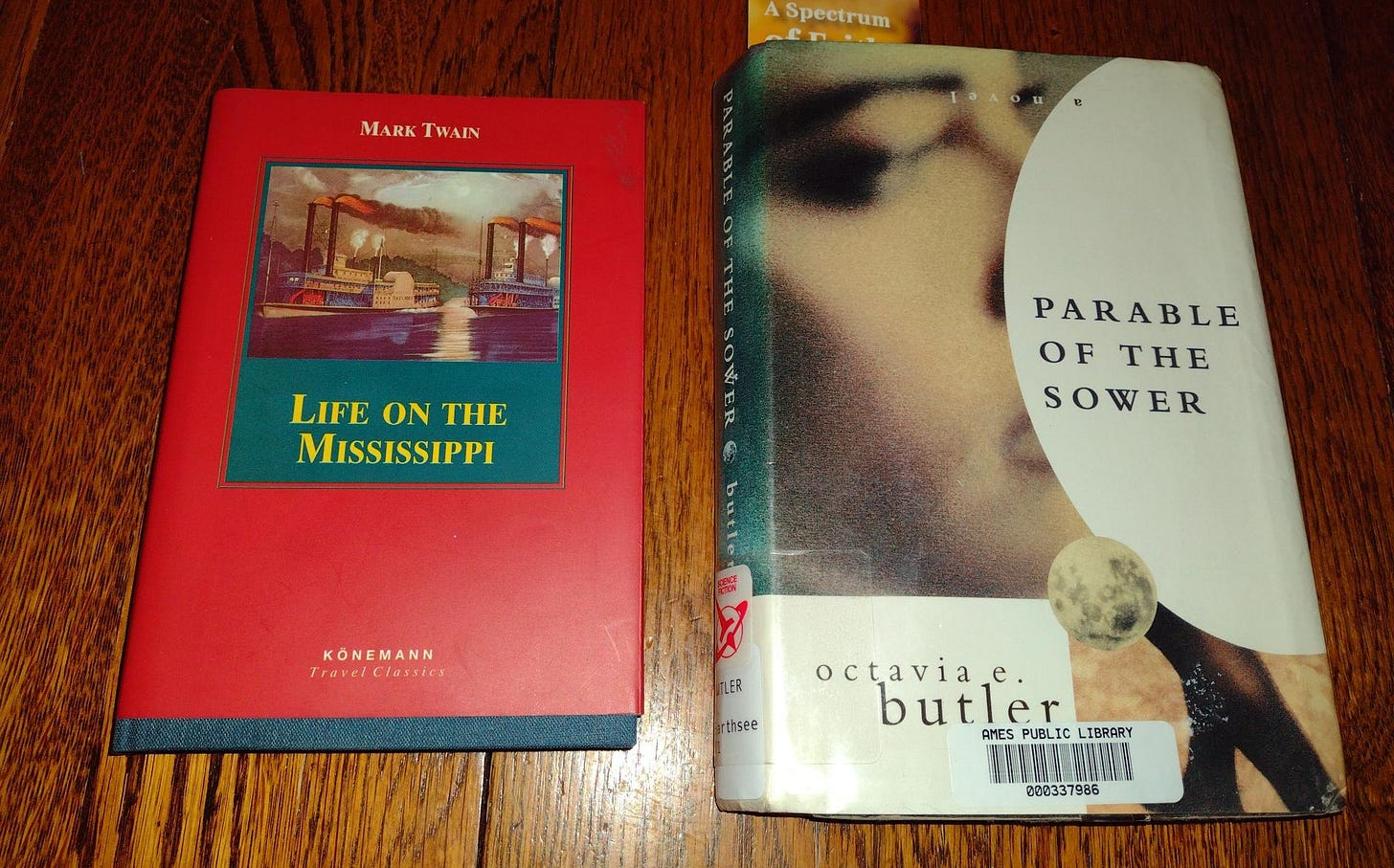

Reviews of: “Parable of the Sower,” and “Life on the Missippi”

Hello to all of good will!

My name is Bruce Gilbert and I have decided to experiment with Substack because trying to communicate longer form ideas on the various Sociable Media out there these days is harder than eating chicken noodle soup with a fork (I almost used a metaphor from the songwriting demigod Jerry Jeff Walker’s immortal album, “Ridin’ High,” but no reason to tip my hand TOO early!)

As to the kind of content you will find here, now and in the future? Obviously, book reviews, probably occasional concert reviews, and meanderings of a somewhat philosophical nature are three likely candidates. I make few promises, other than to say that this will be regularly irregular.

Onward to the content, as they say.

Commonalities of the Timely & the Timeless

So, yes, I’m like a lot of you, I read multiple books at the same time (well, not literally, but you know!) I could blow smoke about some grand reading plan, but it’s pretty much a coincidence that I read “Life on the Mississippi” (by Mark Twain) and “Parable of the Sower” (by Octavia Butler) at the same time (they are the 5th and 6th books I’ve consumed so far this year).

I will give each devil their due directly, but what do these books have in common? After all, one is a nineteenth century history-facing recollection of misadventures aboard various steamboats and environs, and the other is a set-in-the-future dystopian tale of life in the 21st century written in the early 1990s.

Well, quite a lot, actually. I’ll limit myself to two common themes: Travel; and Surviving a Brutal Existence

Travel as a mode of life runs as a theme throughout “Life on The Mississippi” and through the last half of “Parable of the Sower” (though even through the first half of the latter book, the protagonist/narrator (Lauren Olamina) is preparing for the inevitable escape from the untenable twenty-first century Los Angeles). This “life on the move” is one of the features that marks both books as undeniably American in nature. Twain even comments on how unfathomable Missippi river life is to his European counterparts who are used to more docile waters and settled surroundings. And while having displaced millions dealing with the vissicitudes of nature and one’s fellow humans are historical and even ongoing occurrences in Asia, Africa, and Europe, they never got to Interstate 5, as Butler’s unfortunates do. This is not surprising, since it’s hard to think of many folk songs outside of the US that extol the virtues of stretches of pavement, while it is equally difficult to imagine US popular music of the last seventy years without such paeans to asphalt. Thus both Butler and Twain plant themselves firmly in the “New World” camp that embraces movement as not only a constant, but even a necessity of life.

Surviving a Brutal Existence would be a redundancy to discuss in “The Parable of the Sower,” but “Life on the Mississippi” has its vissicitudes throughout as well; Twain is known for his deadpan humor, but sometimes he leaves out both the humor and the pan. A comical series of interactions with a senior riverboat pilot takes a twist when the senior pilot refuses to even share the same northbound boat with Twain; so the young Sam Clemens follows in another boat a few days later, only to discover that the earlier steamboat was blown to smithereens by its own boilers, killing most on board, including not only the senior pilot but also Clemens’s younger brother. Couple this with unemotional reportage descriptions of the periodic catastrophic flooding of the Mighty Miss, and any notion that either of these works takes an overly romantic view of their respective subjects is soon disspelled.

“Parable of the Sower”: Eerily timely

Turning next to the “Parable of the Sower,” I will admit that this is the first time I have read a long-form work by Octavia Butler. She is famous as a writer of science fiction, and for good or ill, I haven’t read much in that genre. However, that is a small handicap for the work at hand; it is much more culturally speculative than “science” speculative.

Reading the book is eerily unsettling for a number of reasons, but here’s the heart of the matter: Written in the early 1990s, the book is set in the following era: RIGHT NOW. As in, all sections are dated, and they begin in July 2024 and end in October 2027. So this leads the reader to a sort of literary parlor game of the dystopic: How accurate was Butler in her speculations?

My answer would be: If you limit yourself to whether she was good at predicting “trends” instead of “actual events” (which I believe is fair, since it IS a work of fiction, after all), she was quite accurate indeed. Among the trends she chronicles are: Widespread environmental degradation; the retreat of the urban population into “walled” communities; devastating fires throughout California; increasing distrust of law enforcement by all citizens but especially by people of color; growing suspicion of “outsiders,” especially from community to community and state to state; and death and destruction at all levels caused by ever-stronger drugs.

One could quibble that we aren’t QUITE as far along the road to destruction as Butler posits, but that’s little consolation: If we’re pretty clearly headed towards Doomsville, the fact that we are ever-so-slightly behind schedule is not all that great of news. Moreover, given the tumultuous micro-epoch we are currently enmeshed in, one could ask if we’re really late to the game at all?

I would say about the only major development that Butler didn’t predict is the ubiquity of the electronic network. Which might lead one to literary Speculation No. 2: If the wonders of the Interwebs HAD been available to the inhabitants of Butler’s work, would it have mattered? Clearly, being able to communicate easily might have helped “the good ones” track each other and avoid trouble; but we are well aware that people of bad intent are (at least) equally proficient at using cell phones and computers as the rest of us, so.. call it a Pyrrhic draw?

“Parable of the Sower” has parallels with other contemporary dystopic works, such as Orwell’s “1984” and Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road.” It would seem, superficially, to have most in common with “The Road” (which it preceded in publication by a couple of decades) since most of both books takes place, well, on the road. I think, however, the parallels with “1984” are well worth contemplating: Both were written about a specified time in the future, and, most importantly, the rusting substructure of the authors’ current culture is still recognizable in both of these future dystopias. So US money is still important in “Sower,” and there are still law enforcement personnel and politicians in place; while in “1984” all of the familiar governmental functions have survived; they have just been transmogrified into surveilling and restricting their populaces, since perpetuating the current government is now the highest value.

“Parable of the Sower” was originally conceived as the first of three books, but only the second (“Parable of the Talents,” written a few years later) has ever been published. I haven’t read the latter yet; I will, at some point, but maybe not for a little while.

Because, in the language of “Sower,” it is (for this reader, anyway) easy to slip into “hyperempathy,” that is, the ability to feel the pains of those around one as one’s own. The narrator/protagonist (an 18-year-old woman named Lauren Olamina) is afflicted with this condition (due to drugs her mother took during pregnancy) and is, as a result, paralyzed temporarily any time anyone (friend or foe) is suffering; and there is a LOT of suffering, on all sides, in this book.

The reader is spared this becoming a re-telling of Mad Max on foot, however, by the narrator’s skills and philosophy. As she is struggling, she is simultaneously developing “Earthseed”, a homegrown philosophy/religion whose main tenet is “God is Change.” Struggling with her hyperempathy and emerging philosophy, at the same time as she struggles with her fellow humans of all stripes, sets this book apart.

As mentioned, for this reader, the book was something of a heavy lift in that emotionally investing in the characters and the plot is a whipsaw empathetic experience. That said, I’m glad I read it, and in these trying times, you should too: The rewards of engaging with these speculative chronicles might just be a broader perspective on our own travails.

(N.B. This book contains descriptions of graphic violence.)

“Life on the Mississippi” Timeless enough?

“It’s too thick to navigate, but it’s too thin to plow” is a lyric about a steamboat pilot from the much-missed John Hartford (probably derived from the Twain remark, “It’s too thick to drink and too thin to plow,” when referring to the Missouri River; that line isn’t included in the present work.) For whatever reason, as I slogged my way through this book and contemplated Twain’s verbiage, I was dogged by Hartford’s phrase.

Too thick to navigate? Unlike some of Twain’s other works (e.g., Huck Finn) there is very little dialog or other recessing mechanisms in this book. So we get paragraphs that run to several pages, filled with (for example) descriptions of every item in a mid-size 19th century manse. Now, this is a common issue for Twain’s contemporaries, whether they be Tolstoi or Dickens or Beecher Stowe. However, us less-hardy modern readers may find this tendency impenetrable at times. (To be fair, early editions of this book were illustrated by lovely pencil drawings of the various landmarks and characters, as they appear in the narrative, that might give the eye a break; my copy didn’t have those, unfortunately)

Too thin to plow? This is neither one of Twain’s funnier books, nor is it as “of a piece” as, say, “Innocents Abroad.” That is partially because it is really two books: Roughly the first half is a chronicle of the wisdom and data that a cub river pilot must inculcate; said pilot must know (at this time, the 1850s) every curve, snag, bank, and islet by sight; and they must know it both going UP and DOWN the river. And this is just where prodigious feats of memory begin: The pilot must also learn to pilot at night, to adjust one’s knowledge base as the ever-fluctuating shoreline and channel continue to mutate; and other details whose mastery can be life-or-death, ad nauseam. (This enhanced memory capacity certainly helped Twain’s development as a writer when he had to abandon the pilot’s life due to the Civil War).

The highlight of this section is Twain’s description of how the daily arrival of the steamboat (in Hannibal, MO in his instance) transformed the waterfront from complete dormancy, to busy-ness comparable to a State Fair midway on a Saturday, and back to dormancy, all in a matter of minutes.

The second half of the book is an uneven retelling of a nostalgic re-tracing of the New Orleans-to-St. Paul river route that Twain undertook in the early 1880s, this time as a passenger. These chapters are an admixture of anecdotes and travelogue-ish relating of impressions of the various towns on his route. The effect of the irregular comic breaks is akin to a dessert traveler arriving at an oasis (or dare I say a steamboat passenger getting some shore leave?) Twain’s thoughts on the funeral industry are a standout, situated (of course) amidst his New Orleans reflections.

Overall, should you read “Life on the Mississippi”? Well, if you haven’t read Huck Finn (either recently, or ever), you should read that first, followed immediately by Percival Everett’s sterling “James.” And if you do read “Life,” find a copy with the illustrations!

N.B. “Life on the Mississippi” contains the N-word several times, plus a number of other offensive references to those of African heritage.